Golden Circle Hegemony

America’s blatant embrace of imperial brinkmanship shares commonalities with the Antebellum South

The American frontier has served as a varied promise to multiple generations of American entrepreneurs and pioneers. Originally, the frontier was a literal description, describing the vast amount of territorial space that existed between the plains and the Pacific Ocean. Many viewed this unexplored territory as holding limitless opportunity for those who were willing to venture into the great and wild unknown.

It was within this mythological idea that the legend of the pioneer and Western man was made. Men of strength, courage, and cunningness rushed forth, heedless of obstacles, toward the promise that was made to them by God and country. The only thing standing in the way of freedom and agrarian independence was ultimately going to be the American man’s conscience and willpower. If he wanted it and if he was willing to sacrifice and work, he could find himself escaping the growing poverty and insecurity of the East.

The self-made pioneer was in part true, as millions ventured westward in search of cheap land and new opportunities. Many started successful farms or ranches; others struck rich in mining or resource development; most, however, ended up in a similar position, merely making ends meet while waiting for the social forces of the East to come knocking. The frontier, beyond the fictional tales and limited stories of success, was ultimately a safety valve for America’s political-economic woes. If inequality, rampant development, or ethnic tensions were too great, many could simply pick themselves up and move west in search of a new life.

The journalist Horace Greeley put this best when he (possibly) wrote:

“Washington, D.C. is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting, and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.”

Unlike our European ancestors, with their limited space and autonomy, the American continent provided an abundance of avenues for independence from authority and urban poverty. Plentiful land, bountiful rivers and lakes, and mountains of Eastern capital made this westward march possible, and with each passing generation, this helped to gradually soothe the political, economic, and social crises of the day. But even the frontier eventually had its limits and emerging political problems.

The land itself was occupied by Native Americans, and from this reality came disagreements over the purpose and means of our manifest destiny. More often than not, our forefathers chose to ethnically cleanse entire swaths of our country, killing and maiming millions over the course of a few centuries. Our dreams of western expansion would not be impeded by human rights or treaty-bound claims to the land.

Even more contentious, as Americans began to move toward this expansive, wide-open, questions over slavery and economy emerged with substantial implications. Would these new lands be free or slave territories; would the introduction of slavery be inherent or one which required democratic consent; did old agreements and compromises on slavery even have to hold as new rulings rendered slaves as full property? As these questions grew more forceful and contradictory, internal changes within America’s two geographic sections emerged, creating separate political cultures that developed very different perspectives on western expansion.

The North, throughout the 1820s to the 1850s, grew massively, with industrialization, capital investment, and transportation technology helping to integrate and augment the region’s comparative strengths and resources. Educational levels, literacy rates, railroads, canals, and various other positive indicators emerged and helped to precipitously expand standards of living alongside the exchange of commerce. For decades, the North, with its Yankee pioneers, expanded westward, bringing with them connections to capital, railroad tracks, and new and exciting professions. It was a regional consciousness characterized by a burgeoning middle class, which was predominantly protestant, moralistic, and willing to embrace the industrial capitalism that was emerging in the Eastern cities. Northerners excelled in the fields of finance, law, industry, and market-oriented agriculture; they drank less and carried with them a far more moral and philosophical view of the pioneering spirit; most saliently, many viewed slavery as an immoral institution that gobbled up land, sullied the labor system, and defied God’s wishes.

Meanwhile, for the South, the first half of the 19th century was one defined by social stagnation and commodity booms. Industrial development did indeed grow, but at a rate which was far below that of the North; where this industrialization occurred was also quite skewed within Southern border states, which were far less sympathetic to the Southern cause. The region lagged in railroad miles, canals, port capacity, and road infrastructure; it was less urbanized, less educated, and deeply driven by the whims of planters. Quite ironically, despite these structural problems, the region was still quite wealthy in some concentrated areas.

Land values and the internal trade of slaves continued to grow, as did agricultural productivity. By the 1850s, coinciding with a boom in the price of cotton and other Southern staple crops, many Southern elites found themselves gaining unimaginable amounts of wealth and capital. Most of this wealth wound up being spent on Northern imports, with furniture, textiles, and agricultural inputs being among the most popular goods. The cost of transporting cotton to markets and industry was also expensive, especially considering the region’s lack of infrastructural investments. But little external pressures or shocks seemed to shift the Southern class from its slave-obsessed pedestal.

Whereas the North was developing a political culture that was embracing industrial development and free labor, the South, throughout the early 19th century, grew to cultivate a culture that was both pompous and deeply insecure. The South’s love of rural agrarianism was to be worshipped as the proper way of doing things; cotton was king, and the region was to lead international trade and politics from atop its moss-covered plantation perch; the North and Europe would be the makers and builders, and all the while, the South would continue to reap the benefits of its superior culture and economy. Southern nationalism skyrocketed during this period, especially among the infamous “fire-eaters” who were maximalists in their love for the region and its institutions.

But this intense love for the region also carried deep insecurities about the future. The frontier had to be made up of slave territories and states to ensure that the Southern model had ample slaves and land, and any deviation from this principle was to be seen as existential. The North was beating and dwarfing the South in most regards, and as this disequilibrium only worsened, the South found itself being surrounded by free states, free people, and free-labor economies, which were all seemingly praying for slavery’s demise. It was a political culture of exuberant pride paired with existential dread, and as the middle of the century approached, these two contradictory feelings began to erode the South’s politics.

Southern maximalism moved westward and attempted to cement slavery’s place by force. Within Kansas, gangs of southern sympathizers formed a competing constitution and state government to ensure that slavery would be delivered by force. Open conflict broke out within towns and farms, and Bleeding Kansas thus emerged. Strict enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, joined by increasingly harsh rulings by the Supreme Court, also followed and only made the political environment more untenable as the South flexed its muscles in an attempt to render the debate around slavery mute.

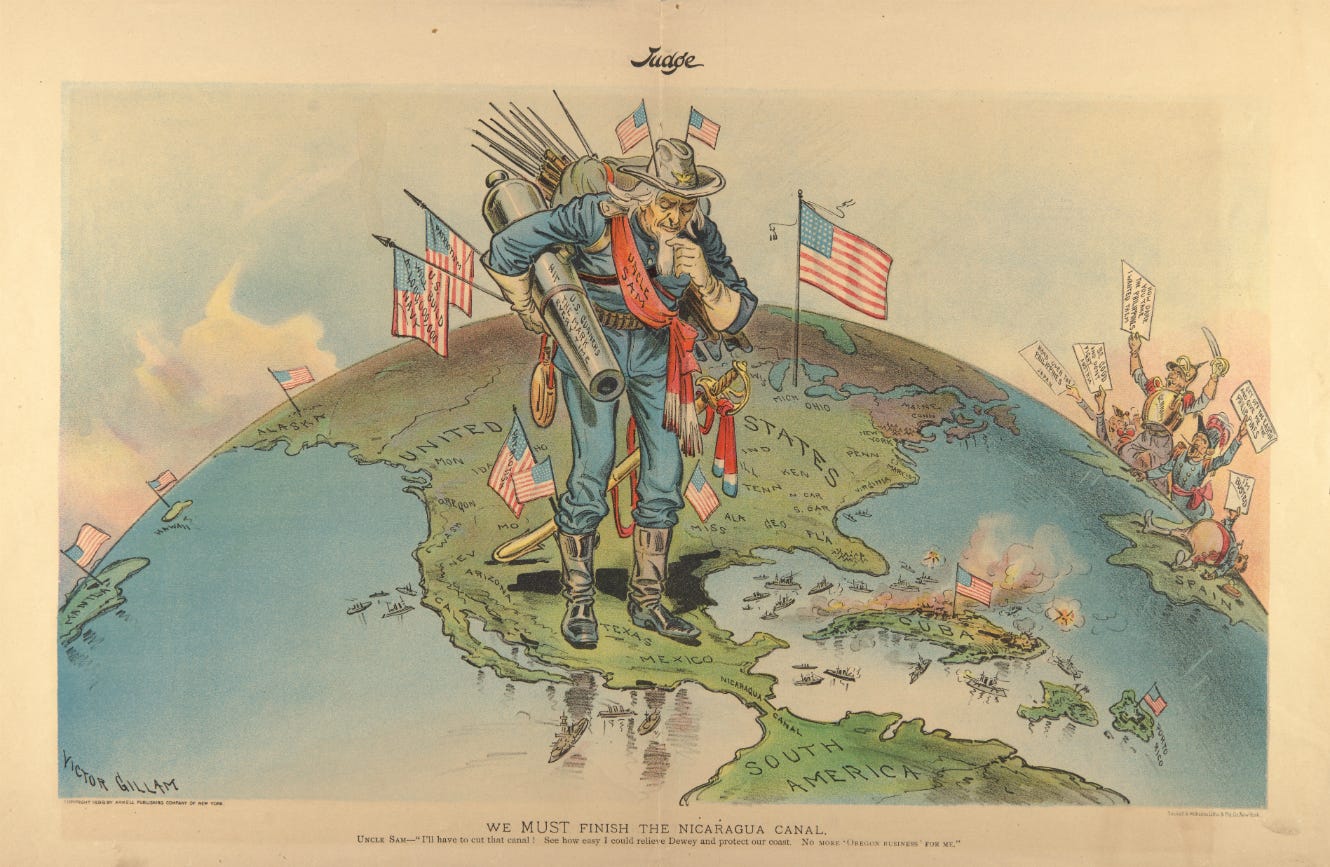

Beyond moving west, the South’s conception of the frontier grew to adopt southward expansion and other forms of imperial conquest. Cuba became a shining star amongst Southern politicians and operatives, with Democratic Presidents Polk and Pierce both attempting to purchase the island from Spain. Some within these administrations, alongside state-level officials, provided material support toward those who were willing to attempt to take these foreign possessions by force. Infamously known as filibusters, swarms of Southerners throughout the 1840s and 1850s tried to invade and take control of Cuba and other countries in Central America. Multiple filibuster-led invasions of Cuba and Nicaragua took place, and all failed to deliver a sustainable occupation or revolution.

The filibuster goal, however, was rather clear: ensure the expansion of slavery. And within the Southern press, these raids and foreign invasions were vehemently supported and praised. Money, arms, and investments were raised by Southern politicians and businessmen in support of the filibusters, and in some cases, these politicians even found themselves leaving their positions and prestige in order to fight for the Southern cause overseas.

Overall, as 1860 neared, the South’s political culture was one of intense insecurity and fear. The region was falling behind politically and economically, and to get ahead and maintain its power, new and extreme forms of force emerged to ensure more land, slaves, and frontiers. Maximalist pioneers drove westward to cement and protect slavery’s position; filibusters invaded foreign nations in search of slaves and new racial hierarchies; and politicians argued for the re-legalization of the slave trade and the legalization of slavery nationally. All were motivated by an intense desire to stop decline and impede their competitor’s rise, and as their actions seemingly failed to deliver the goods, the only options left became increasingly radical and militaristic. By 1861, the South was in open rebellion, and the frontier was now being contested through the barrel of a gun.

The contemporary United States shares many parallels with the Antebellum South’s chaos. Obviously, the Trump administration is not openly declaring its support for the slave trade, but its policies have indeed begun to take on a more imperialistic and nationalistic bent. Calls for bombing and occupying Cuba have grown, as have calls for the US to take control of Greenland and Panama, potentially by force if necessary. Near-century-long alliances and norms have been discarded within a matter of weeks, and all for the purpose of expanding territorial reach and influence. China’s position and control over vital resources is rising, and many within the government have come to view these events as existential.

A stable or secure hegemon does not need new frontiers predicated on land annexation or resource control to ensure its security. Instead, what we are now witnessing is what the South experienced in the 1850s, and what American conservatism has continued to feel since the early days of the Cold War. The roots of Southern and Western conservatism, which have continued to shape conservative politics since the days of Goldwater, have finally made their way onto the global stage, loudly eschewing the norms and practices which have sustained our global order for decades.

American First isolationism has not emerged, but rather a kind conservative American foreign policy driven by fear, moral panic, and resentment. It is shaped by a distaste for Europe, an intense hate of Chinese competition, and a strict hierarchical view toward race and global politics. Bellicosity is to be utilized, and international institutions are to be clipped and weakened. Moreover, America’s place within the hemisphere must be maximalist and absolute, with democratic governance and allies being viewed as weak rather than helpful. Any government, businesses, or group that stands in our way will be defeated, and any and all regional resources will now be considered under vassal status, requiring our permission for their use and export.

The South’s vision of the frontier required more land and expansion to ensure its survival, and within the Trump administration, a similar logic is seemingly being applied. While direct ownership may not be necessary, our government has made it clear that the US must have nonpareil access to regional resources and trade. Countries should compensate us for the right to use our markets, and dissenters must be made an example of. In order to survive the rising power of China and the global south writ large, the US has entered into a mindset that expansion abroad is preferable to domestic investment or innovation.

The goal is not internal improvement or a sound industrial policy, but instead the insatiable drive for land, resources, and profit which can then be allocated to oligarchic friends and investors. Much like with the South, new lands will be given to modern-day plantation owners. Promises of new libertarian cities and utopias are already being drawn up, as are plans for new trade routes, mines, and industrial hubs. It is a political economy predicated on imperial expansion and annexation, and all in the name of a maximalist death drive against decline.

Much like with the South, this plan for the frontier is doomed to fail. Short-term obsessions with capital accumulation, speculation, and annexation will not build a competitive economy, nor will they bring regional peace. Modern-day filibusters, now through the form of influencers, private military contractors, and tech gurus, will likely embark on campaigns to highlight which countries or areas should be American. As internal conditions deteriorate and feelings of insecurity only grow, these maximalist tendencies will mutate and grow more destructive. The beast of imperial consumption is not sustainable. Eventually, it will begin to consume itself as its lack of investments and overt contradictions become too much to endure. America’s place within the world is now far more controversial and in decline, and as the imperial hegemon continues to lash out, more chaos should be expected within the coming years.